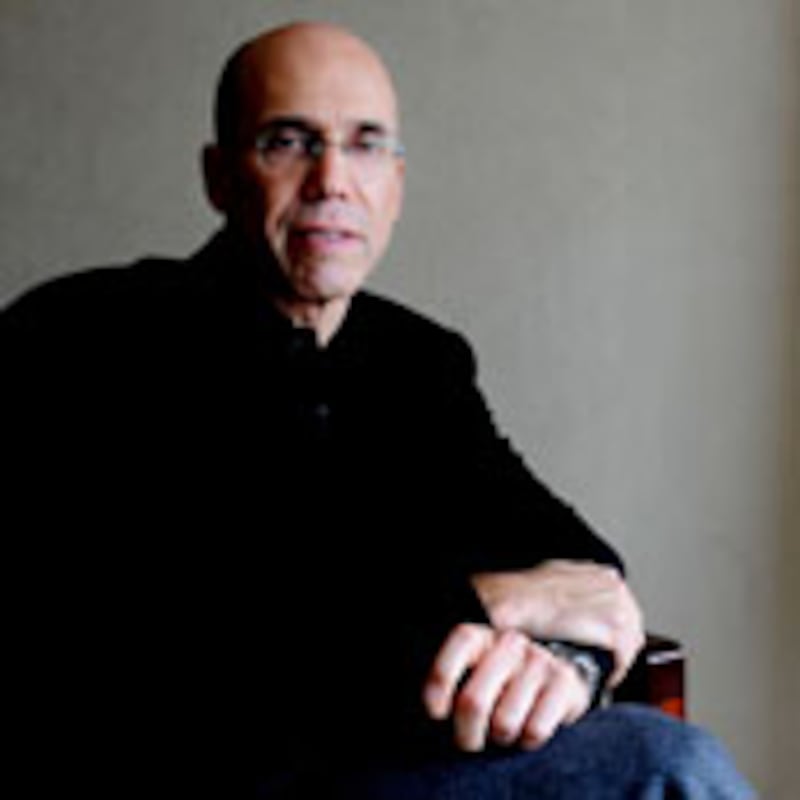

It’s been a miserable year for animation titan Jeffrey Katzenberg, who was marooned from his former producing partners and fleeced by Bernie Madoff. Now, oddly, comes troubled Bank of America with a $175,000 promotion to offset ticket prices for his new movie.

You can look at a glass as half empty or half full. But however you look at it, Jeffrey Katzenberg’s cup has contained a bitter brew of late. In a year that has much of Hollywood anxiously fretting over the future, the man who was once the K in DreamWorks SKG—planted impressively between Steven Spielberg and David Geffen in that uber-powerful acronym—finds himself separated from his former partners as he fights through a particularly trying period in his long career.

Katzenberg has hyped his upcoming movie, Monsters vs. Aliens, opening on March 27, as a crowning triumph for his DreamWorks Animation studio. But getting this film released in the manner that Katzenberg had wished—and promised—has been a daunting challenge to the end. This morning, Wall Street analyst Rich Greenfield sent out an email revealing a potentially controversial promotion for Monsters v. Aliens, in which Bank of America is offering coupons to offset the premium that customers must pay (an extra $2 or more per ticket) to see the film in 3-D. Greenfield notes that he is unaware of any B of A announcement regarding this offer; he only learned of it through chat on Twitter. "We find it odd that a bank that just received $45 billion in government aid is paying for consumers across the U.S. to see a movie in 3-D vs. 2-D at no extra cost," he writes. "We also wonder whether the presence of [DreamWorks Animation] President Lew Coleman helped [the company] convince Bank of America to enter into the promotion, as Coleman is a former vice chairman and CFO of Bank of America."

“We acknowledge and accept that with public support, taxpayers are demanding that banks be more conservative in their spending and rightly so,” says a Bank of America spokesman.

In an exclusive interview about the movie with The Daily Beast earlier this week, Katzenberg did not mention his deal with B of A even when asked specifically about the premium charges. (When we asked Katzenberg to address the B of A promotion this morning, he replied that he had no information on it.)

Bank of America spokesman Joe Goode told us this morning that promotion is costing the institution $175,000. "We acknowledge and accept that with public support, taxpayers are demanding that banks be more conservative in their spending and rightly so," he says. "I also believe that banks have been criticized for activities that are of benefit." This one fits into that category because it "rewards customers for their loyalty at very little cost to the bank." Goode says B of A is pursuing promotions "in a strategic and cost-effective manner to support and grow our business and generate returns for investors—a group that now includes the American taxpayer." As for the connection with former B of A executive Lew Coleman, he says that was not relevant to the deal. "DreamWorks helps us reach a key customer demographic—women and families," he says.

It's not clear whether the B of A promotion will grow into a fully developed kerfuffle (there are so many for Congress and the cable channels to choose from). But for Katzenberg, this is just one more potential trouble spot among the many that he has been facing. Just fifteen years ago, the diminutive Katzenberg cast a huge shadow in Hollywood, a member of the very exclusive club of studio chiefs. As chairman of the Walt Disney studios for a decade that ended in 1994, he made his most lasting mark by reviving the studio’s moribund animation division, cranking out hits from Little Mermaid to Lion King. After an epic battle with his boss, Michael Eisner, he ended up on the street—but not without a huge settlement and a posse of powerful friends. Within a few weeks, he had teamed up with Spielberg and Geffen in a bold effort to create Hollywood’s first new studio in decades. The plan was to build a media powerhouse and in its early years, DreamWorks seemed to be living up to its promise—kicking off the Shrek franchise and winning three consecutive Oscars for Best Picture ( American Beauty, Gladiator, A Beautful Mind).

Since then the dream has pretty much shattered. As DreamWorks foundered, the animation division had to be split from live-action into a separate company. At this point, all that's left on the live-action side is Spielberg’s production company, and even he is having trouble raising cash. Last month, Spielberg made a deal to distribute DreamWorks films through Disney—which means that for the foreseeable future, the DreamWorks partners cannot be re-united. There simply is no room at Disney for another animation label or for Jeffrey Katzenberg.

Instead of presiding over a media empire, Katzenberg now finds himself chief executive of an animation company that releases a couple of movies a year. DreamWorks Animation has defied the odds by making with hits including Shrek, Madagascar and Kung Fu Panda, but clearly this is not what Katzenberg had in mind a few years back when he led reporters on a tour of the property that was to be the future home of the DreamWorks media conglomerate. "He thought of himself as a master of the universe, as an industry statesman,” says one associate. “He’s now realized he’s off to the side. He’s not at the cool kids’ table.” Like other studios, the company faces tough challenges in this economy.

Manwhile Katzenberg has other woes to contend with:

Last December, Katzenberg was shocked to learn that he had been fleeced by Bernard Madoff for millions, an as-yet unspecified number clearly in excess of $20 million and, according to one source, as much as $50 million. “This is extremely painful and humiliating for me,” Katzenberg said soon after in an interview with CNBC. “It has done extraordinary damage to my philanthropy.”

Then, in February, DreamWorks announced sharply lower fourth-quarter earnings thanks in part to the sagging market for DVDs that is afflicting the industry as a whole.And just when he was hoping to be celebrating a great triumph—nothing less than the transformation of the whole film industry—Katzenberg has been forced to admit when his much anticipated Monsters vs. Aliens is released, its impact will be less than advertised. During the past year, insisting that the 3-D film would be a game-changer on a par with the advent of talking pictures, Katzenberg had pledged that as many as 5,000 screens would be converted to 3-D technology in time for this film’s opening. Now he acknowledges that fewer than 2,000 screens are ready (meaning that a great many theater goers will see the film the old-fashioned way, in 2-D).

As recently as February 24, Katzenberg said that customers would be charged a $5 premium on each ticket to see the film in 3-D. But theater owners wouldn’t go along with the plan. Now, he acknowledges that theaters will charge a premium but it will average out to a bit more than $3 per ticket. That should cut into the extra $80 million boost in profit that the company had hoped to reap on a hit movie thanks to the 3-D experience. (And making the film in 3-D adds an estimated $15 million to the cost.)

If all of the above weren’t enough—et tu, Jack Black? Katzenberg has lavished money and attention on the Kung Fu Panda star, only to be repaid by Black’s riposte as he presented the Oscar for best animated film this year. "I make more money doing animation than doing live action,” Black quipped to the show’s 36 million viewers. “Each year I do one DreamWorks project, and then I take all the money to the Oscars and bet it on Pixar."

And then he handed the golden statuette to Pixar for Wall-E.

When I called him to ask him about his annus horribulus, Katzenberg agreed to talk, with the proviso that we could only discuss Monsters vs. Aliens and the 3-D revolution that has yet to materialize. But he doesn’t sound daunted by any of these setbacks. Katzenberg is a bit of an alien himself when it comes to super-human resilience (in fact, one executives who works with him observes a resemblance between Katzenberg and the alien in the movie's trailer).

Katzenberg is almost freakishly self-confident, and even despite his string of failures, he can console himself with his successes. Jack Black is right: DreamWorks animated films make more money than the more critically celebrated Pixar’s. And the company has established three rich franchises in its relatively short history: Shrek; Kung Fu Panda, which pulled in more than $630 million around the world last year; and Madagascar (the sequel to which grossed $585 million).

So Katzenberg's films may not win Oscars, but they score at the box office. Notwithstanding the shortage of 3-D screens, Monsters vs. Aliens is likely to open big. And Katzenberg says he has no regrets about having hyped the film as 3-D’s coming-out party. “The world is a changed place,” he says. “I mean, c’mon. Really, I think it’s pretty amazing that we’re going to end up on 50 percent more screens than any 3-D film before us. . . . It’s certainly more than enough for us to make a return on our investment and to be a genuine proof-of-concept.”

Katzenberg also expresses no embarrassment about his much-maligned Super Bowl promotion—an ambitious plan in which Dreamworks distributed 150 million pairs of special glasses across the country so super bowl viewers could watch a 90-second ad for Monsters vs. Aliens. The ad alone cost $9 million, but the reviews weren’t very positive. When USA Today ranked the top 50 Super Bowl commercials, the pricey DreamWorks pitch didn't not make the cut. One reader commented, “The 3-D thing is the worst Super Bowl experience since the clothing malfunction.” The next day, the CEO of the company behind the technology issued a statement assuring consumers that the 3-D effect in theaters is “a quantum leap better than what they saw on TV.”

But Katzenberg insists the ad was considered a failure “only by a handful of snarkers” because it created huge awareness of and interest in the film. “Are there people that took shots at it? Yes,” he says. “Does the consumer feel that way? No. It is not possible to have been more effective.”

That kind of hyperbole is pure Katzenberg—the kind of outrageous self-confidence and bluster that has often bedeviled him but has also sustained him throughout his career. Whether it will continue to help him as much as it hurts is anyone’s guess.

Kim Masters is the host of The Business, public radio's weekly show about the business of show business. She is also the author of The Keys to the Kingdom: The Rise of Michael Eisner and the Fall of Everybody Else.