To be scrupulously honest I only met Noël Coward twice in my life, and then briefly, but I heard so much about him at home when I was growing up that I always felt I knew him well. That is in large part because my mother, Gertrude Musgrove, was an English stage actress of some renown, who had begun her career in Charlot’s Review in London, singing and dancing, along with Noël Coward and Gertrude Lawrence, and then won something of a reputation for herself as a comedienne in Terence Rattigan’s French Without Tears in 1936. She knew and adored Coward, whom she always referred to as “darling Noël,” and they both shared the same high spirits, the same excited shouts of “Dah-ling!” across the room at first sight of each other or any British actor or actress, the sparkling gaiety, the dressing room chatter and gossip, and above all the determination to be the life of every party, behaving in public as if the '20s and the '30s had never ended, and as if Champagne for breakfast or the Café de Paris on Piccadilly after the theater were still the only way to live. Once she moved to the United States, she lived in theatrical hotels, the ones where visiting English actors stayed when they were working on Broadway or “on tour,” like the Drake or the Gorham in New York City, and saw Coward often, and in her old age she named a succession of pug dogs after him. She knew by heart, and could sing all of Coward’s songs, and so my mother singing “I’ll See You Again,” is as fixed a memory of my childhood as the Blitz.

For people of my mother’s generation in some ways Coward, despite his penchant for world traveling, was England: Noël Coward and Winston Churchill were somehow central, each in his own way, to the idea of England between the wars and during the war. In fact, Churchill single-handedly managed to delay Coward’s knighthood for many decades, overruling the desire of King George VI to knight him for writing, producing, co-directing with David Lean, and starring in the war-time film In Which We Serve, which was based on the naval exploits of Captain Lord Louis Mountbatten, RN, who would go on to become Admiral of the Fleet the Earl Mountbatten of Burma and uncle (as well as royal matchmaker) of Prince Phillip, and was of course, like everyone who mattered, a friend of Coward’s. My mother also shared with Coward the experience of having a fiercely ambitious “stage mother” determined to put her child “on the stage” at the earliest possible age, and to remove from her prodigy every scrap of identification with the suburban middle-class.

Noël Coward was born in Teddington, Middlesex, his father an unsuccessful piano salesman. The family was eventually obliged to move even further down the social scale to Battersea, on the wrong side of the Thames, and open a lodging house, worse still, but by the age of 12 Noël had made his first professional appearance as Prince Mussel in a review called The Goldfish at the Royal Court Theater, and never looked back to his lower middle-class roots. The brittle accent, not so much upper-class as beyond upper-class, the clipped diction, the lean, pantherish elegance, the astringent wit, the expressionless face, almost Chinese when seen from the front, or perhaps a carved Kabuki mask, were all in the process of development, and would shortly produce a unique and instantly recognizable figure that never seemed to age, a British landmark, rather like Mount Rushmore for Americans.

By the age of 21 Coward was already an established actor in musicals and Mayfair drawing room comedies (he did not aspire to do Shakespeare or “serious” theater), had written two unsuccessful novels and several much more successful plays, and had visited New York and performed on Broadway. His appearance was fixed: the elegant clothes, the beautiful hands, always gesturing with a lit cigarette, the sleek hair, the silk dressing gown, the gold cigarette case. He was one of the central figures among “the Bright Young Things” of Mayfair, whose behavior was beginning to cause such horror among those who were older, or less clever, or easily shocked by young women in short skirts and with bobbed hair smoking cigarettes, and by elegant young men of ambiguous sexual tastes wearing Charvet ties and silk shirts. By25 he was already famous as the author of Hay Fever and The Vortex, and on his way to becoming an international social celebrity and had created a momentary scandal, his first, but not his last, when one of his plays was banned by the Lord Chamberlain.

One of the many paradoxes about Coward was that while his plays, his songs, his lifestyle, and his attitude toward sex, life, and marriage, were all intended to infuriate the English middle-class, and for a time did so, he would eventually become the darling of just those people he was trying to mock. The brittle, worldly wise dialogue, the pose of jaded sophistication and languid indolence, the implied toleration for ambiguous or illicit sexual relationships, all of which seemed so shocking in the mid-'20s and produced a wave of indignation and moralizing, soon produced self-satisfied laughter in the audiences rather than an astonished and embarrassed breathlessness, and made Coward a rich man, a pillar of the Establishment rather than somebody who was chipping away at its very foundations. Before long, the British middle-class began to see themselves in Coward’s characters, and Coward, as he aged (ever so slightly and reluctantly) and his hairline receded, began to admire in the middle-class just those qualities that he had set out to make fun of—never was any rebel so quickly won over, or, for a long time, more warmly embraced.

Thus the man who had written The Vortex went on to become author of hit after hit, on both sides of the Atlantic: Private Lives, Cavalcade, Design for Living, Blithe Spirit, Tonight at 8:30, Coward’s output was prodigious, and the more remarkable because he not only wrote his plays, but generally played the leading man in them. By the time the war broke out, Noël Coward and his favorite actress Gertrude Lawrence were practically a national institution, and even an Anglo-American one, for they were just as much appreciated on Broadway as in the West End. As for his songs, which he not only wrote but performed (for nobody else could get that perfect diction and timing right, or make sense of those staccato rhymes): on after the other, “The Master,” as he became known, popped them out: “Poor Little Rich Girl,” “I’ll Follow My Secret Heart,” “Mad About the Boy,” “Twentieth Century Blues,” “Mrs. Worthington,” “Mad Dogs and Englishmen” (who else could do justice to a line like: “But Englishmen detest a siesta”?), “Play Orchestra Play,” “You Were There.” Each sing was more brilliant, more brittle than the last:

“You were there I saw you and my heart stopped beating You were there And in that first enchanted meeting Life changed its tune, the stars, the moon came near to me, Dreams that I dreamed like magic seemed to be clear to me, dear to me. . .”

It used to be said that an entire generation of Americans made love to the singing of Frank Sinatra, and in the same way a whole generation of English people of a certain class met and fell in love to the music of Noël Coward, and modeled their conversation after that of Noël and Gertie:

“ELIOT: You love me too, don’t you? There’s no doubt about it anywhere, is there? AMANDA: No, no doubt anywhere. ELIOT: You’re looking very lovely you know, in this damned moonlight. Your skin is clear and cool, and you eyes are shining, and you’re growing lovelier and lovelier every second as I look at you. You don’t hold any mystery for me, darling, do you mind? There isn’t a particle of you that I don’t know, remember, and want. AMANDA (softly): I’m glad, my sweet. ELIOT: More than any desire anywhere, deep down in my deepest heart I want you back again—please— AMANDA: (putting her hand over his mouth): Don’t say any more, you’re making me cry so dreadfully.”

He could make his audiences cry, and make them laugh, uproariously, as with the song “I’ve Been to a Wonderful Party” or “I Wonder What Happened to Him?” (“Whatever became of old Tucker?/Have you heard any word of young Mills/Who ruptured himself at the end of a chukka/and had to be set to the hills?”), and perhaps hardest of all with the British, made them laugh at themselves. At first he put a foot wrong in the war, and was attacked in the press for writing “Don’t Let’s be Beastly to the Germans,” which was banned from the BBC, but was rescued by the fact that Winston Churchill loved it—he and President Roosevelt argued about the words, and Churchill insisted on Coward’s singing it over and over again, until Coward was sick of it. (The fact that Coward had neglected to declare his American earnings to the Treasury was what doomed Coward’s knighthood, not his songs, still less than his unconcealed and unapologetic homosexuality in a world where it was a legal offense, and he and Churchill remained friends and mutual admirers.) Coward’s wartime plays were a triumphant celebration of the English middle class from which he had emerged into the glare of celebrity, praising their patient, stolid courage under fire, epitomized by This Happy Breed and Cavalcade, as well as by the song “London Pride.” All of this now seems a little like propaganda, as does In Which We Serve, but it was at least propaganda in a good cause, and was totally sincere: Coward admired the British spirit, celebrated it, in some measure, for a time, defined it.

Dabbling in espionage at the request of Churchill, making films, keeping up British morale, Coward survived the war with his reputation increased, but like Churchill, was rejected in the austerity of postwar Britain, sunk into poverty, socialism, and seriousness. He came to be seen as flippant, pandering to the upper classes, celebrating a world of inequality and class consciousness, and although his output remained high, he was increasingly valued as a performer in Las Vegas, with friends like Marlene Dietrich, rather than a British cultural asset, and spent more and more of his time out of England, in Jamaica, where he built a house, or in America, a British institution respected more abroad than at home, and in perpetual flight from draconian British taxation. He finally received his long delayed knighthood in 1970, but by that time he had come to seem like a frail and quaint reminder of another age, even—unbelievably—old fashioned!

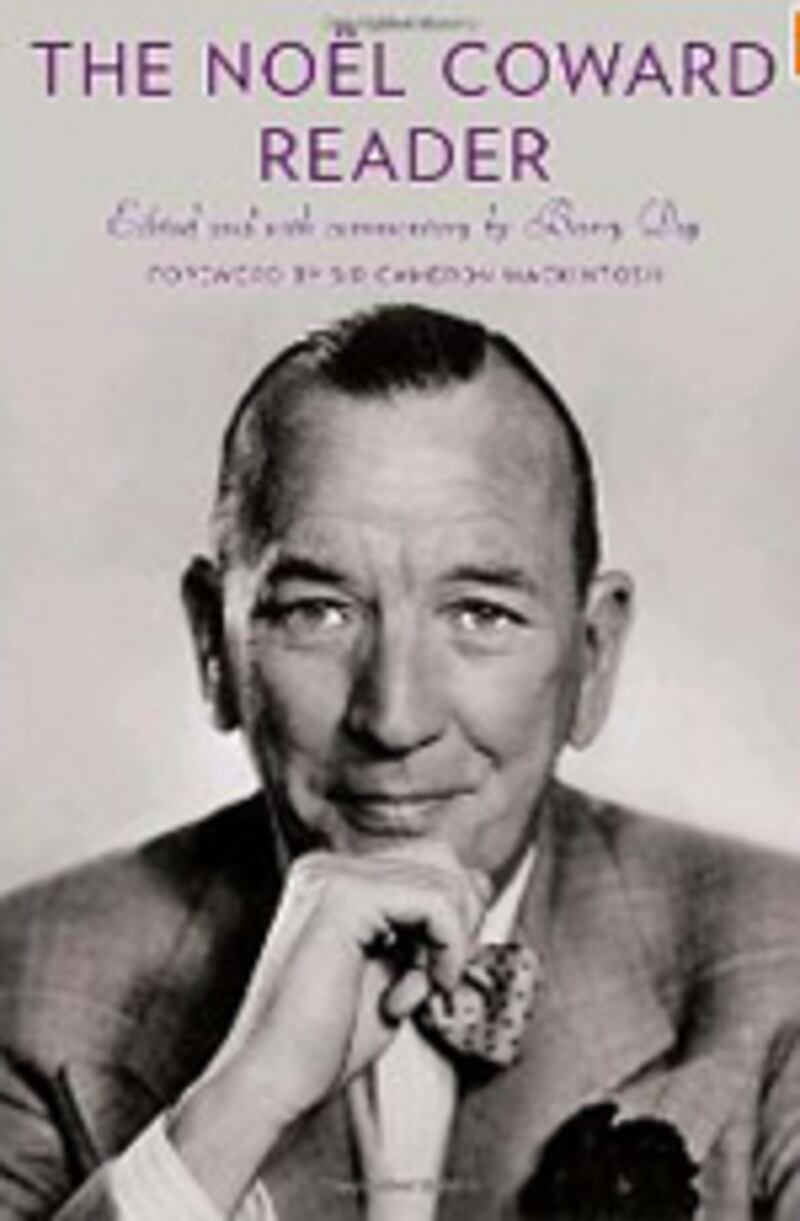

In The Noël Coward Reader, Barry Day has collected a wonderful selection of the Master’s work, plays, fiction, songs, brilliant nuggets from an incredibly rich life’s work that ought to be placed under the Christmas tree of anyone who admires Coward, or is interested in the theater, or has even the slightest curiosity about English life and letters from the end of the First World War to the end of the Second. Better, and more important, it is all great fun, and a reminder of what an extraordinary talent Coward was, as well as a reminder of an age that was so vastly more literate, witty, elegant, and dare one say, courageous than our own? There is nobody in “Show Business” today that rivals Coward’s talents, for, as his friend Admiral Lord Mountbatten said of him: “There are probably greater painters than Noël, greater novelists. . . greater librettists, greater composers of music, greater singers, greater dancers, greater comedians, greater tragedians, greater stage producers, greater film directors, greater cabaret artists, greater TV stars. . . If there are, they are 14 different people. Only one man combined 14 different talents—The Master. Noël Coward.”

Only one indeed, and the best of his best work is gathered here, as fresh and readable as ever, in a volume that is full of wonderful things, and equally wonderful illustrations. Buy it, darling!

Plus: Check out Book Beast, for more news on hot titles and authors and excerpts from the latest books.

New York Times bestselling author Michael Korda's books include Ike, Horse People, Country Matters, Ulysses S. Grant, and Charmed Lives.