Overheard conversational scraps set the mood at the opening of the New York City MoMA exhibit, Club 57: Film, Performance, and Art in the East Village, 1978-1983.

“I’ll never forget when your guy borrowed my drum kit and bled all over it,” one fellow told another, jocularly. A woman behind me said sourly “I got what was left of him.”

The party turned out to be a time machine, with known faces swimming in and out of vision. Was that John Waters? Yes. Ann Magnuson, a ringmaster of the event, in something glittery? Of course. Joey Arias? Fab Five Freddy? Kenny Scharf, Patti Astor, Lypsinka, Animal X? You thought they were going to stay home? Jeffrey Deitch? Tony Shafrazi? Natch.

“Everybody who is alive is here,” somebody marveled to me.

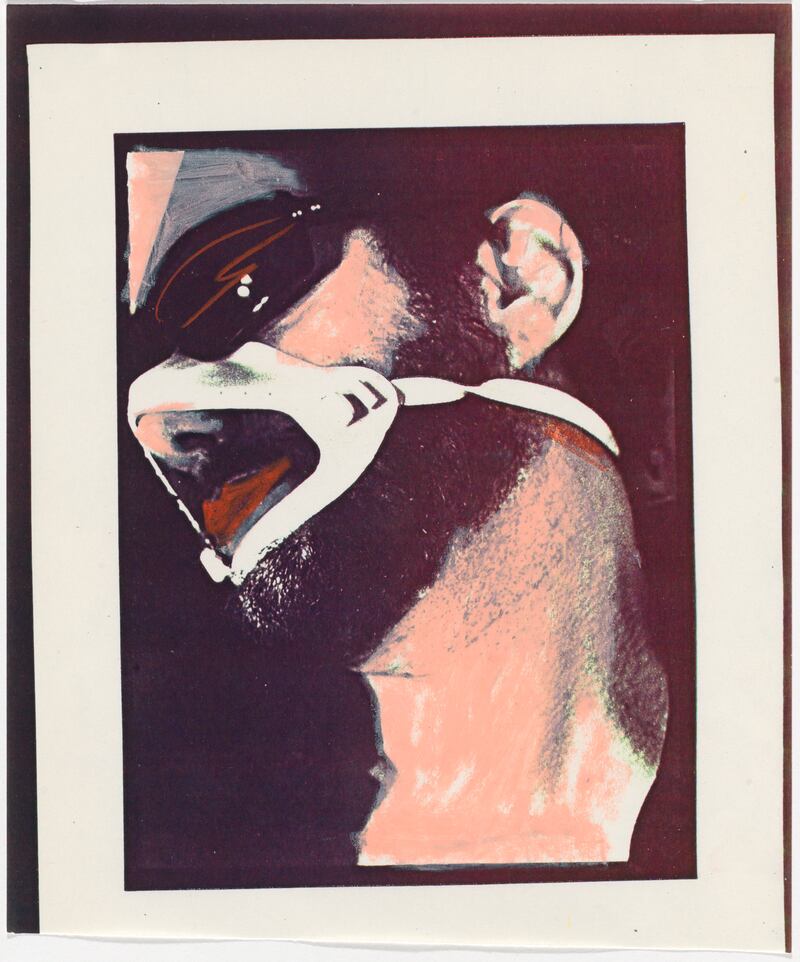

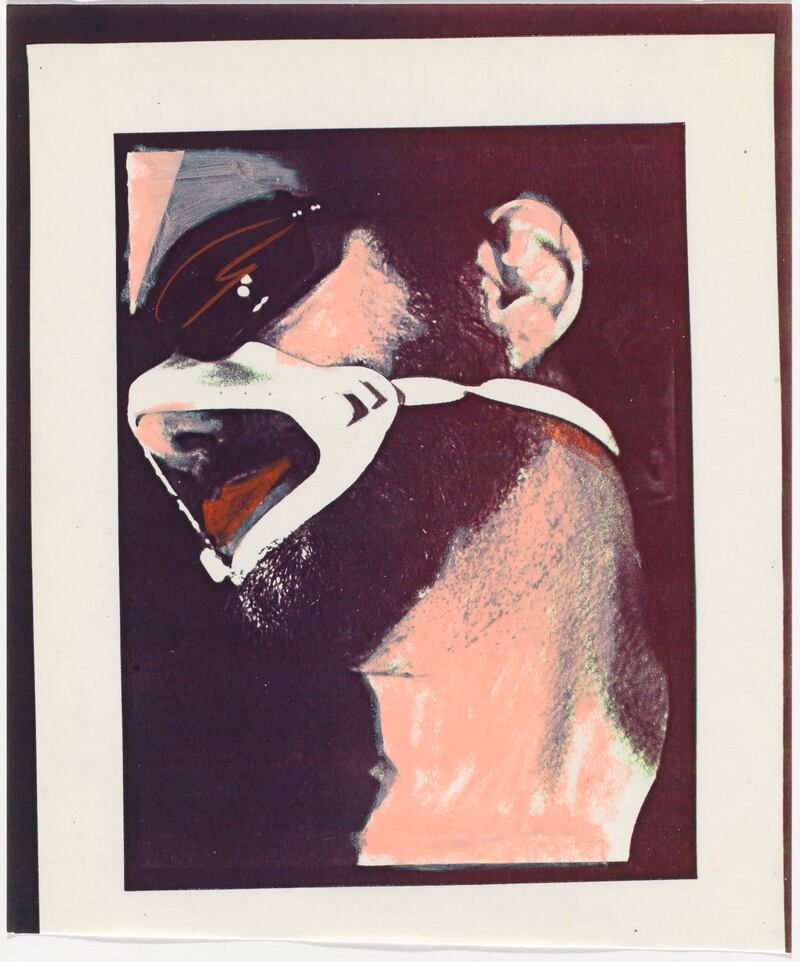

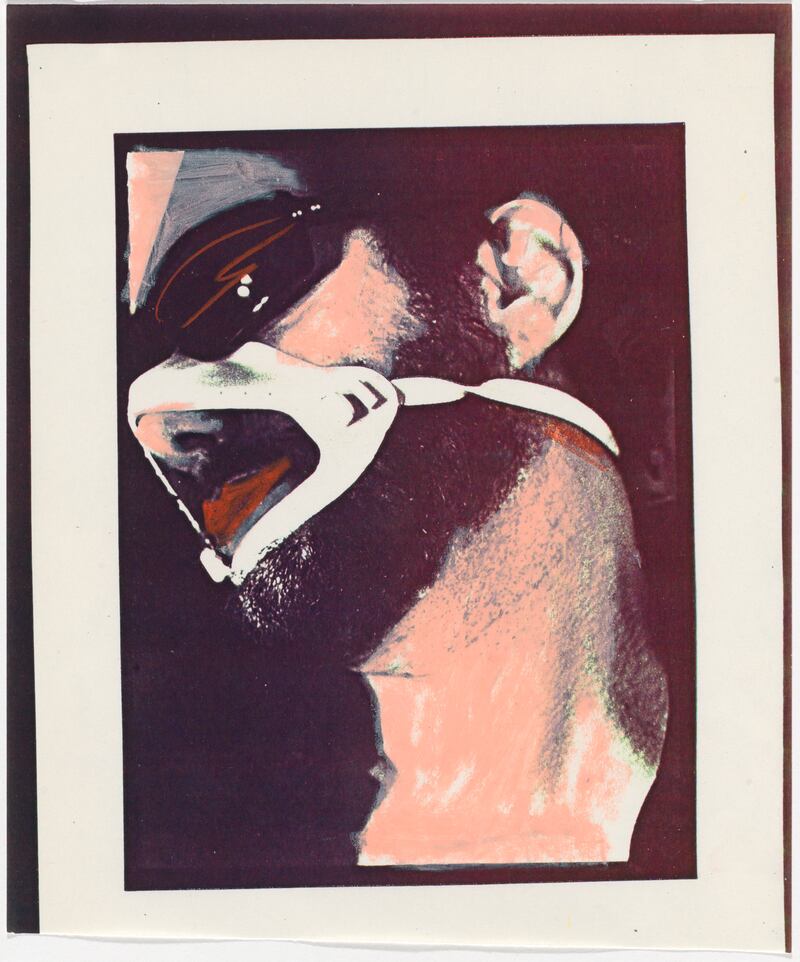

Tabboo! (Stephen Tashjian) (American, born 1959). Self-Portrait, 1982. Acrylic on found advertising paper.

Courtesy the artist and Gordon Robichaux, New YorkAnd the show? The materials were ephemeral, do-it-yourself, gender-playing and gleefully outrageous, but flirty rather than hard-core, and meticulously put together into a show as multi-faceted and structurally sound as a beehive.

Club 57 was founded by Stanley Strychacki, a Polish-born entrepreneur, as a fundraiser for the Holy Cross National Church on 57 St. Mark’s Place, and it pulsed from 1978 to 1983. So what does visual evidence of high times in a church basement a third of a century ago tell us now?

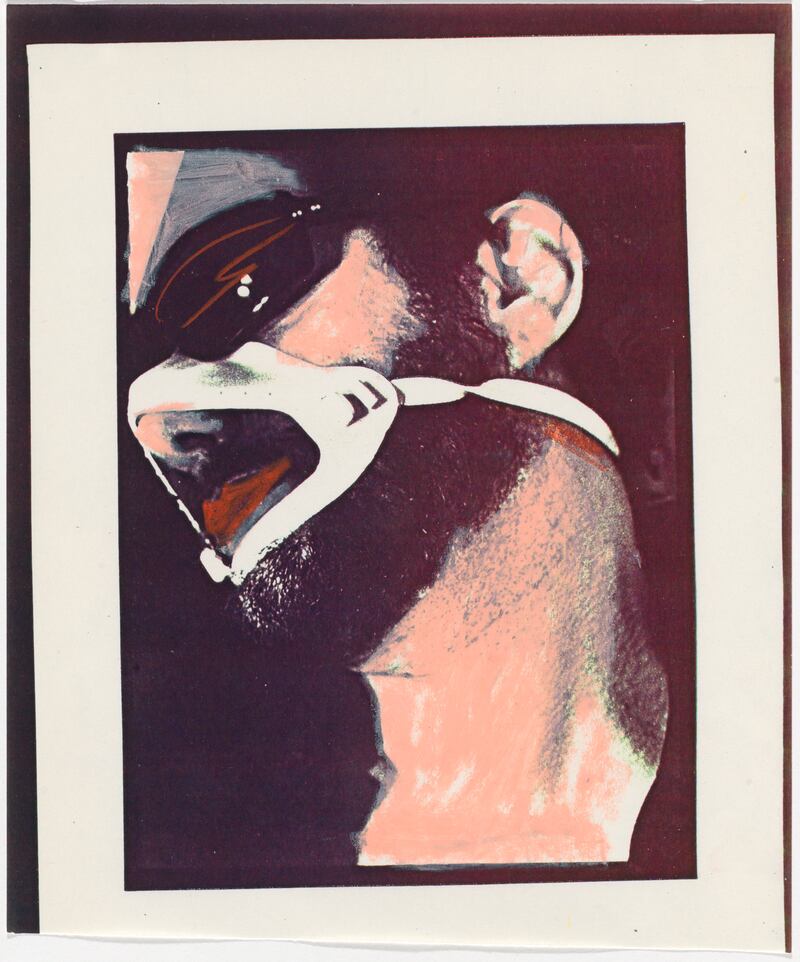

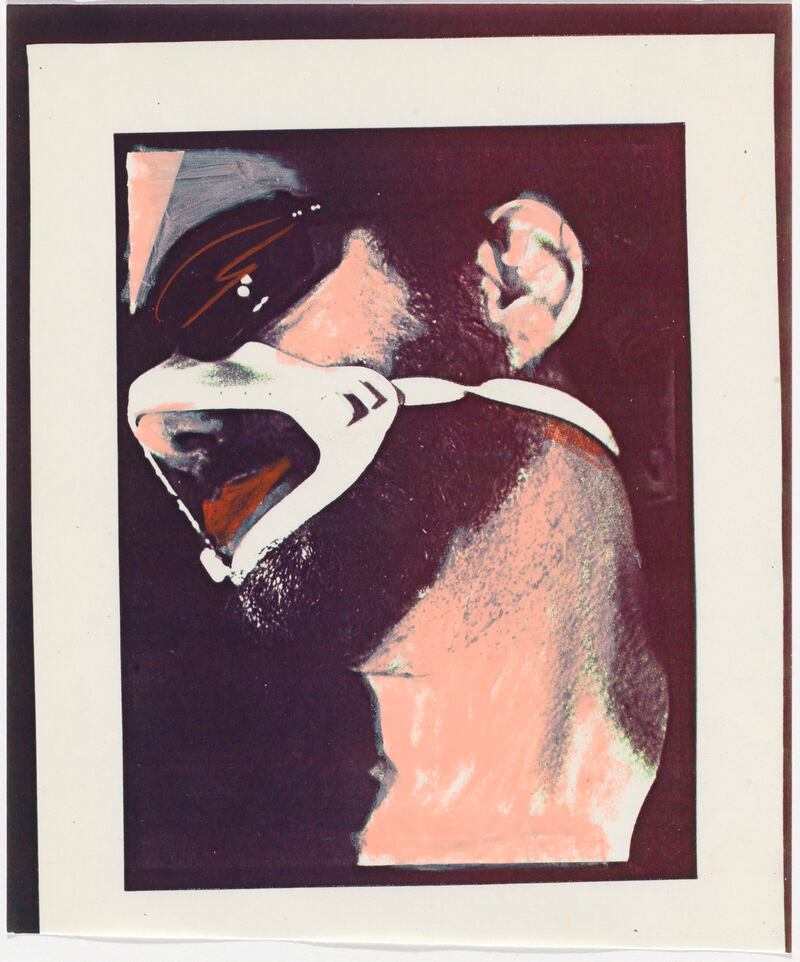

Gerard Little. 1980.

Photograph by Robert Carrithers. Courtesy the artist.Rewind moment. The New York to which I moved in the mid-’70s was supposedly a high risk place. Bankruptcy had been dodged in 1975, but that same year Mayor Abe Beame had let it be known that he was thinking of laying off 10,000 uniformed police; this, even though the city was routinely portrayed as a sci-fi dystopia.

It was a period when a cover of New York magazine showed a knife slicing through a house, and when the Lower East Side was such a No Go zone that it wasn’t a stretch that one local hang-out named itself for a brutal civil war, Downtown Beirut.

Kenny Scharf (American, born 1958). Having Fun. 1979. Acrylic on canvas. Collection Bruno Testore Schmidt.

Courtesy the artist and Honor Fraser Gallery, Los AngelesAnd that was just where Club 57 flourished for five deliriously silly years.

So to the show. There are several dominant presences here, some because they have earned their spot in the Klieg light of art history–like Kenny Scharf, who got to install his Cosmic Closet which glimmers here like a luminous sugar plum, as well as paintings and a flyer for the Times Square Show of 1980, the event arguably launched the Lower East Side art world as a raucously in-your-face fact of life.

Keith Haring (American, 1958–1990). Untitled (Cabinet Door for Joey Arias). c. 1980. Acrylic on cabinet door, double-sided.

Courtesy Joey Arias, © Keith Haring FoundationAlso observe the vitality of the work of Keith Haring. He organized many Club 57 exhibitions—such as his Xerox Art Show of 1986, his Anonymous art show and his Gems of the Gutter, which was of stuff found in the street—which had been both brilliantly inventive and a nose thumbing at the money games of the Uptown art world.

It was good to see work by the late Dan Asher, a still under-recognized artist, but generally painting is not a strength of this show.

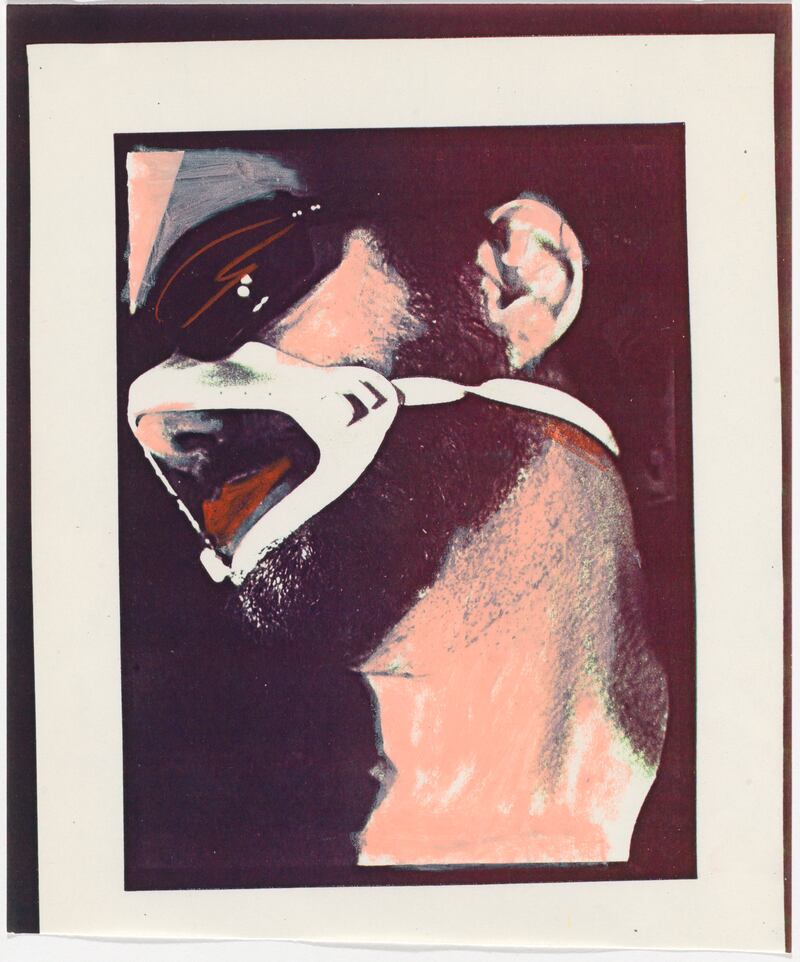

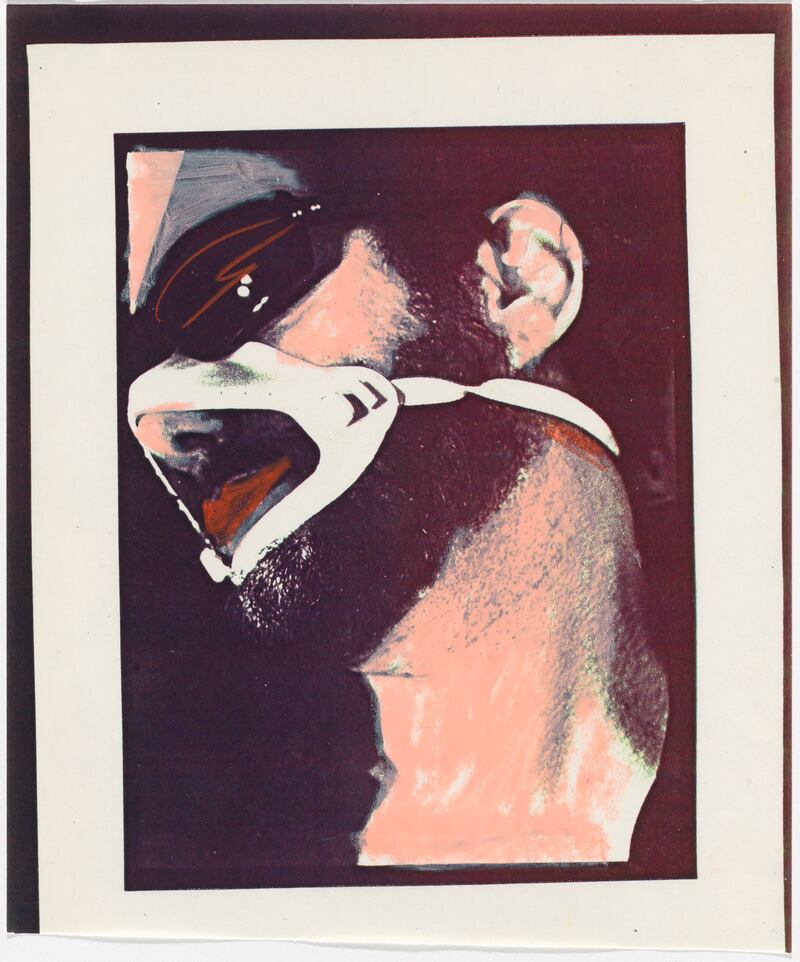

Anney Bonney (American, born 1949). Process art from Shattered (Male Bondage: Carl Apfelschnitt), 1978–79. Xerox collage. The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Department of Film Special CollectionsIt is however in keeping with spirit of Club 57, which was both clannish and anti-hierarchical, that much of the work is by folk who were not working artists but were very much on the scene, such as Ann Magnuson who shows collages, and Patti Astor, who would open the seminal Fun Gallery with Bill Stelling before Club 57 had run its course, and is represented by original art for the flyers of five movie screenings.

There is also work by John Sex and Klaus Nomi. Nomi, Sex, and Keith Haring are long dead of AIDS, as are others here. So, like just about any group show of the period, this is also a memorial.

Bruno Testore Schmidt (Italian, born Brazil, 1954). Allan, 1981. Watercolor and ink.

One unexpectedly effective element is the show’s use of a historical accident: Namely the obsolescence of the Medium-High Tech of the IBM Selectric, pre-Internet era. M. Henry Jones shows wheels of photographs he had painstakingly hand-cut and hand-colored between 1977 and 1979 to make Soul City, his animation of a performance by a stalwart Club 57 band, The Fleshtones.

This was a couple of years before MTV, a decade before Photoshop. It looks terrific. Another element is the generation-old telephone messages kept by John Mozzer, listenable to through a headset.

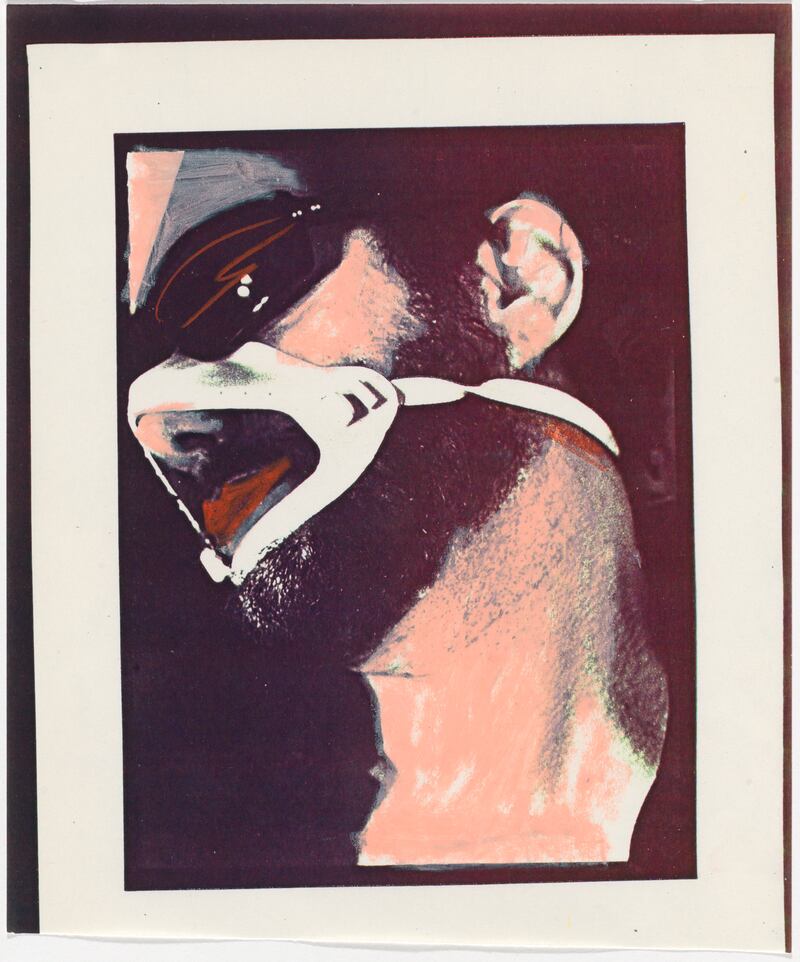

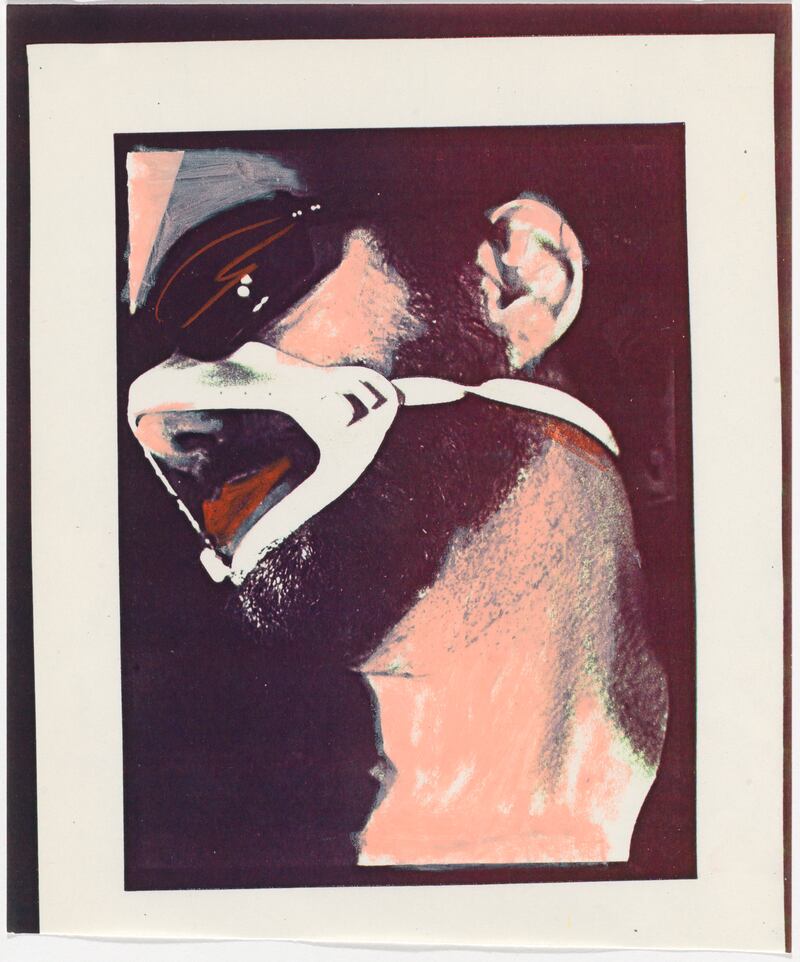

The Rule of Mr. Klaus #19, 1980. Photograph by Anthony Scibelli, from a series for a photo-roman written by Peter Nolan Smith (pictured).

Collection Peter Nolan Smith, courtesy the artistIn one he chats with John Sex about Lisa Baumgardner, creator of the zine, Bikini Girl, which is also here. Long-gone gossip springs to life. “It was something to do with ovaries,” said Sex of an ailment of hers. “She had a straight job for quite a while…” Baumgardner too is dead.

There is a wall of paper material from the Keith Haring Foundation, including tabloid pages—“Paralyzed Dachshund is Cheerful”—and innumerable flyers and magazines, which also predate Photoshop.

Ann Magnuson in video stills from Tom Rubnitz’s Made for TV, 1984. Video (color, sound), 15 min. The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Purchase funds provided by The Contemporary Arts Council. Courtesy the artist and Video Data Bank“They used Zip-A-Tone. That was a kind of a dot screen you applied to the graphic,” Jones said. Tech advances can be a problem when an artist has used the earlier forms, like Duchamp’s bicycle wheel and Dan Flavin’s neon. “I had to find a toner-based Xerox,” Marlene Weisman, one of the artists in the show told me.

Well, I’m of an age to remember making copies that faded to stinky near-nothingness, but the plus is this. Just as venerable sports cars and clunky old space capsules look way more captivating that the new, the outdated tech at MoMA looks oddly seductive.

Jennifer T. Ley (American, born 1953). She Doesn’t Cry Over Faded Bouquets Anymore, 1979. Pastel and pencil on color Xerox. The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Department of Film Special CollectionsAnother pertinent element is this. Ronald Reagan was inaugurated in January 1981. There are, of course, Conservative artists, as there are Conservative rockers, but it is hardly the norm.

Hung close to the entrance of the show there are some pages from the Soho Weekly News, asking: “What Is Your Opinion of President Elect Ronald Reagan and How Do You Envision the Next Five Years?” On another wall there are a couple of collages, featuring Reagan as well as Don Black, Head Wizard of the Klu Klux Klan, in front of a cross burning in Tuscaloosa, Alabama.

Ann Magnuson in video stills from Tom Rubnitz’s Made for TV, 1984. Video (color, sound), 15 min. The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Purchase funds provided by The Contemporary Arts Council. Courtesy the artist and Video Data BankSome contributors to the Soho Weekly News questionnaire were more hostile than others to Reagan, but none wholly consumed by fear and loathing, and some were jocular. I mentioned this to a woman at the show. “We knew him as an actor,” she said, blithely. (Not a bad actor in our modern sense either. Do I need to point a finger here?)

The exhibit includes a weekly changing bill of movie and video fare, including a film club that will show various notoriously clunky movies—Planet of the Vampires, The Gore Gore Girls—clear through till mid February, and a video program that promises everything from Haring and Scharf to The Scary Truth About Cockroaches and Landlords by Tessie Chua and Sur Rodney Sur.

Another attention-getting element in the “Club 57” show is an event flyer. It shows a cartoony head, with fingers stuck in ears, above the headline “STOP CLUB 57.” It is dated 1981, and asked the block association to come to a meeting in another neighboring church, St. Cyril’s.

This attempt to close down the club was unsuccessful, but just two years later Stanley Strychacki, angered by a wave of heroin usage that was disabling his staff, closed the place down anyway.

Club 57: Film, Performance, and Art in the East Village, 1978-1983 is at NYC’s MoMA, until April 1, 2018.