The timing of House of McQueen couldn’t be better.

New York Fashion Week is upon us, a favored time of year for human peacocks to bestride the streets of Manhattan. Darrah McCloud’s play, at The Mansion at Hudson Yards and booking through Oct. 19, is about the life and work of the legendary British designer, who died by suicide aged 40 in 2010. It may well become a stopping off-point for the absolutely fabulous between runway shows, champagne receptions, and night-time shenanigans.

And it is fashion, though not on stage—criminally—that is the best bit of the show. Off-stage, just past one of the bars in the maze-like warren of corridors of the venue, is an exhibit of 27 original McQueen creations. Make time to search it out and delight in McQueen’s artistry, especially if you didn’t see the excellent Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibit, Savage Beauty, which the museum mounted in 2011.

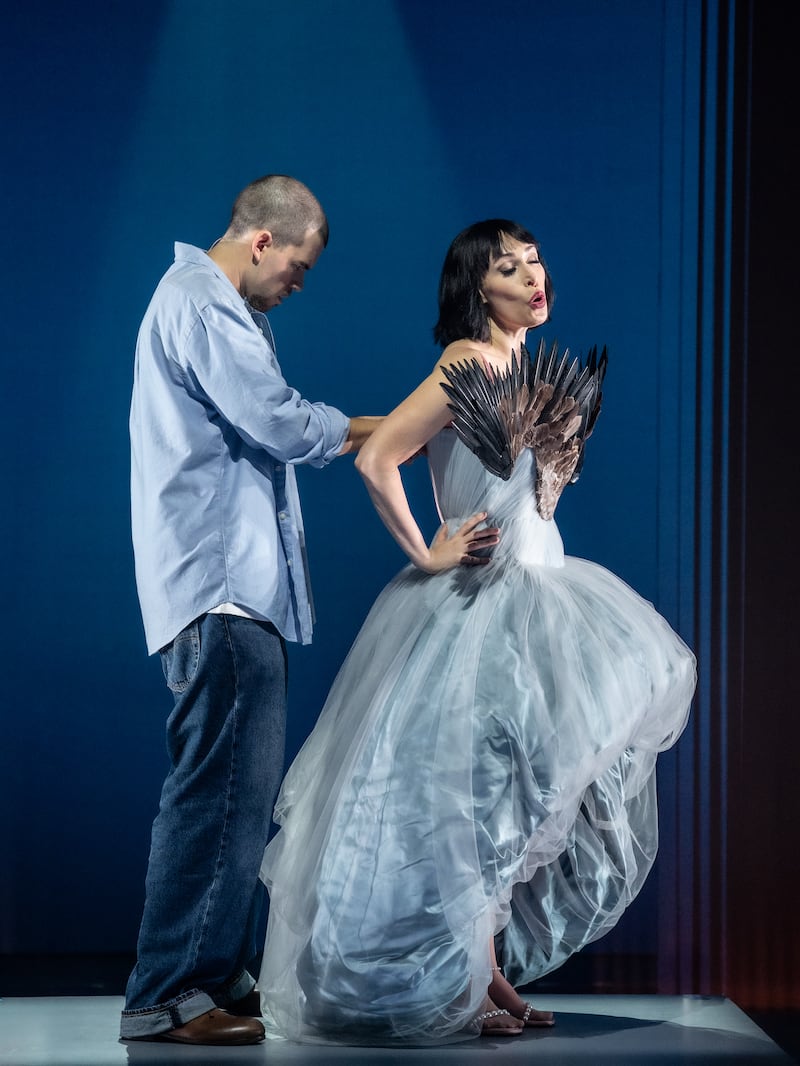

During the play, presented in collaboration with Gary James McQueen, Alexander’s nephew and Creative Director, you only see glimpses of McQueen’s designs on snatches of video.

There are undoubtedly practical, legal, and other reasons why we do not see these clothes on stage, but in a play about such a major fashion figure it is a very loud, absent ghost at the feast. The fashion in the show is unmemorable, even when it comes to recalling the eccentrically clad Isabella Blow (Catherine LeFrere), McQueen’s muse, close friend, and patron saint of all fashion peacocks.

The play, directed by Sam Helfrich, darts between eras and modes of storytelling, not really settling on a compelling through-line. We hit the major McQueen life moments and personality traits—difficult childhood, abuse, working class background, the snobbery he initially endured, drugs, homophobia, sexual expression, his taking over at labels like Givenchy, suicide—but they jangle in a baffling muddle on stage.

We are told how the violence Lee (as his family and friends knew him) had seen and experienced when young had informed McQueen’s creative vision, and how torn-up material and wrecked-looking models were so controversial at the time, but we never feel the thrill, dazzle, and shock of these moments, or understand the formation, marshaling and command of McQueen’s influences.

Instead, House of McQueen feels cut-and-paste, a cartoon more than character study, and this coalesces into a tone of detached, fashionable remove, with the cast facing us and relating bits of story, or each other in staccato outbursts to move bits of the story along. There are all the accoutrements of fashion—swagger, people being bitchy (though not really b----y, sadly), loud music—but little nuanced analysis to make sense of McQueen’s life and art.

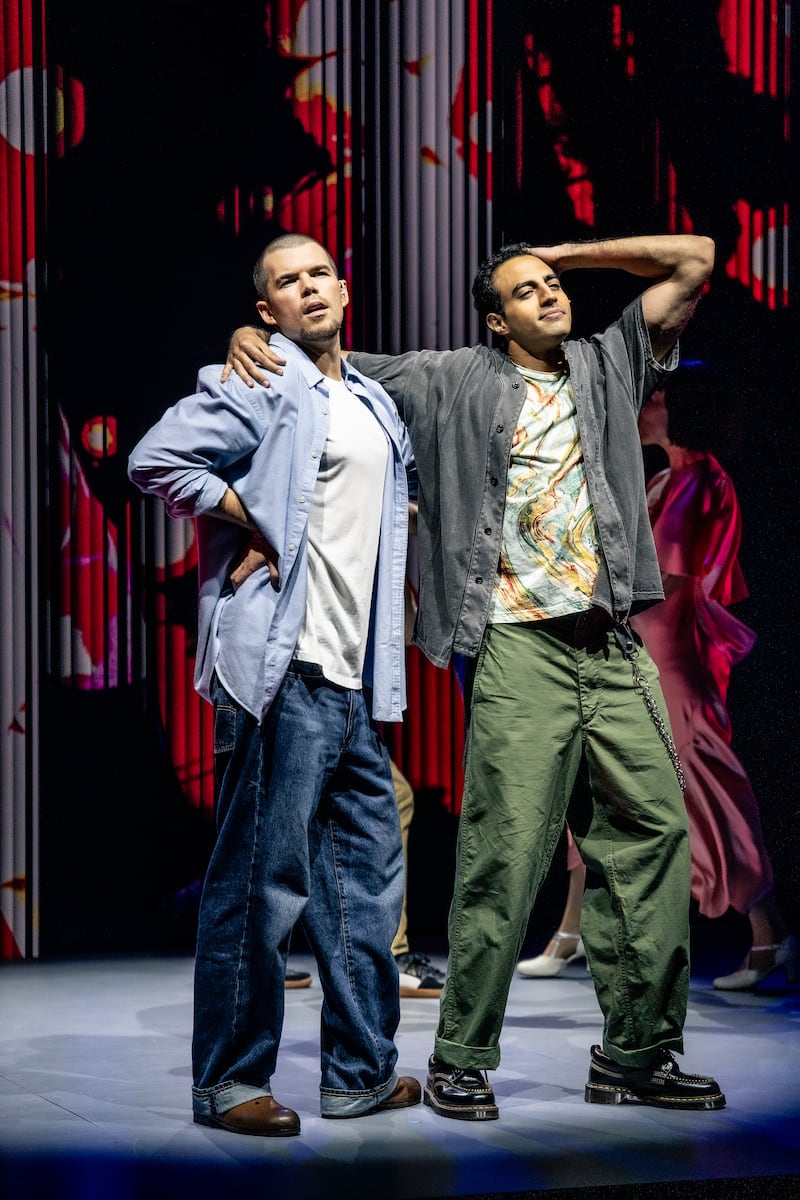

The show’s welcome and much-needed anchor is Bridgerton star Luke Newton, playing a white T-shirt and blue-jeaned McQueen, who brings an impressive depth and presence to the designer, and to the roiling inner forces that comprised and ultimately broke him.

But Newton cannot surmount the play’s odd creative choices, such as the silly news reports that inform us of real-life moments such as the debut of McQueen’s “Highland Rape” collection—related with the breathless, stone-faced urgency of conventional reports of wars and economic collapse. With video and projections, the play toys with the spectacle of its subject, seemingly hovering between documentary and parody—never quite sure which to alight on. (Some of the attempted British accents are, hmm, not good.)

Another recurring idea is to have McQueen’s beloved mother Joyce (Emily Skinner) interviewing him about his work, but these encounters are flattening not illuminating. McQueen was a hard-working, complex genius, but the play reduces him to a damaged demi-thug, raddled by demons. If you see the show and scratch your head at who he was and what happened during his life, the 2018 documentary McQueen, showing on Netflix, may be a useful companion piece.

The play features McQueen’s family, Blow, and some figures in his private life, but never in ways that reveal much about their relationships.

Who were his boyfriends/husband? That guy? That guy? Was Blow in love with him? What was their relationship really about? Dependency, love, need, transaction—all of the above? Why were they both so depressed and suicidal? What actually happened when he was a kid? What or who were the true dark forces in his life? Who or what was McQueen beyond being troubled and determined to shock in his work? Who or what was keeping his family away from helping him?

The play may know its subject, but doesn’t convey that knowledge effectively or dramatically. It either wrongly assumes we know it all, or thinks itself above telling a conventional story about a person who so brilliantly defied convention. The result is like dipping in and out of surrealism-laced Wikipedia entries—or, as might be seen a lot this week in New York’s finest restaurants, a fashionista stabbing absently at escapee peas on a plate.