Two musical notes repeat. They are The Warning. A warning that trouble is coming—trouble with lots and lots of teeth.

Composer John Williams came up with that simple two-note alarm and won an Oscar for it—and for the rest of his powerful score for Jaws. The film also won for film editing and for sound.

The two notes, an E and an F, evoke the screechy violins in Alfred Hitchcock‘s Psycho. That’s fitting. The master of suspense was a huge influence on the film, director Steven Spielberg explains in Jaws @ 50: The Definitive Inside Story, premiering on National Geographic July 10 and streaming on Disney+ and Hulu the following day.

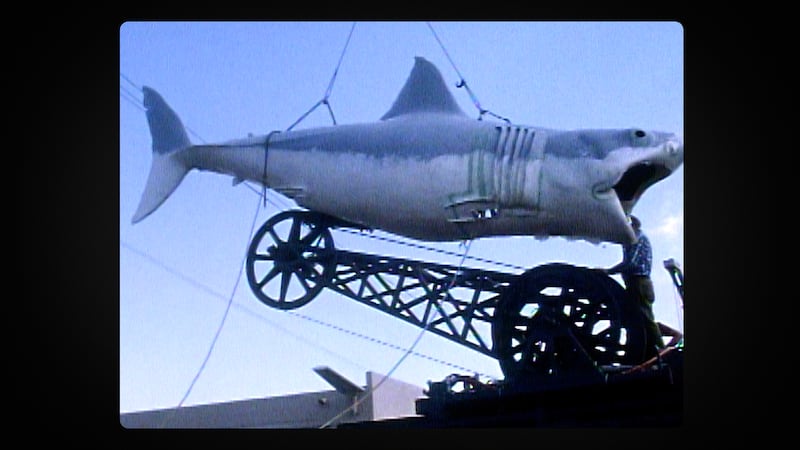

Although the finished film is a perfect thriller, its production was anything but smooth sailing. Even on the set, the script was being rewritten. Shooting fell far behind schedule, and the mechanical shark—nicknamed Bruce, after Spielberg’s lawyer—kept breaking down.

Spielberg had already proven what he could do with pacing and intrigue on Duel, a 1971 TV movie about a threatening truck driver. But Jaws was only the 27-year-old filmmaker’s second theatrical feature, and his first with a big budget and tricky special effects.

Yet, somehow, it all worked wonderfully.

“A movie that I thought would really end my career is the film that really began it,” Spielberg says in the documentary.

Although the mechanical Bruce was temperamental, he came through for his close-ups. Other scenes of sharks gliding through water are real (those two notes just played in your head, didn’t they?). Ron and Valerie Taylor, divers, filmmakers, and conservationists, captured that footage, seamlessly edited into the movie.

“I was as hungry as the shark was to tell the story of Jaws‚" Spielberg says. “I didn’t know how it would be done, but my instincts told me it needed authenticity so the shark wouldn’t be laughed at.”

Laugh? We could barely breathe. Watch it again today. It remains as powerful, even when you know the ending. This is a perfectly paced film, whose fans now include several generations of filmmakers.

“There have been movies made since using CG sharks that aren’t nearly as good,” says James Cameron (Avatar, Aliens, Titanic), and a National Geographic explorer at large. “It was those actors and that moment in history with that director, and no one ever having seen anything like that before. Some films just hit that perfection. They become sharks, the perfect machine.”

I recently rewatched the film, brilliantly, just before heading to the beach. And no, I didn’t go in the water that day. Jaws has that effect on people. It always has. When it first came out, anything involving water was suspect. Forget about the ocean. People were genuinely uneasy in pools. Even running through an open fire hydrant felt dangerous.

It wasn’t logical. But it was true.

“Horror is the thing that shouldn’t be but is,” director Guillermo del Toro observes in the doc. “The laws of physics and the universe are upside down.”

The phenomenon began with Peter Benchley’s bestselling novel. It was the sort of book that several people would be reading on the subway, and conversations started about where you were in the book. Former Cuban President Fidel Castro loved Tiburón (shark in Spanish), and said it was a perfect metaphor for the corruption of capitalism.

Benchley was delighted by this, although he couldn’t persuade his Doubleday Publisher to use Castro’s quote as a blurb.

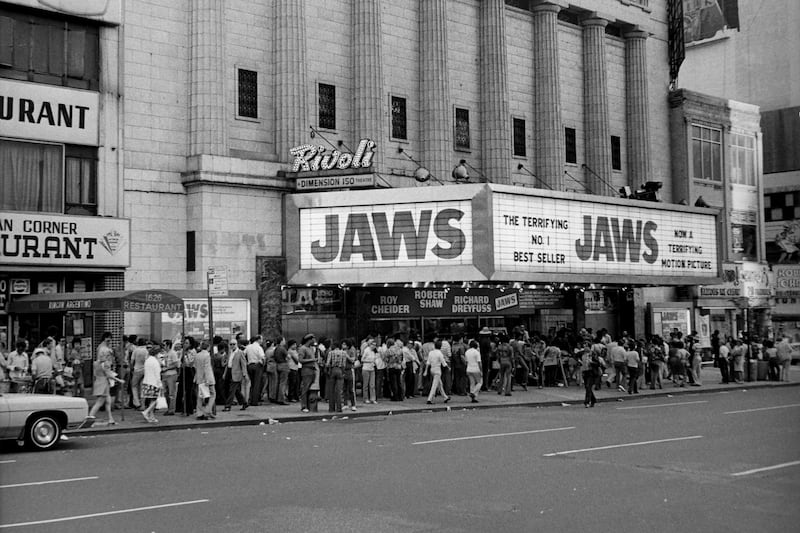

The mania only increased when the movie debuted on June 20, 1975, becoming the first modern blockbuster. Sure, there were massive hits before: The Birth of a Nation (1915), The Godfather (1972), but Jaws was different. Lines wrapped around blocks. People went back to see it repeatedly. It was the first movie to break $1 million. Half a century later, the tally is $1 billion.

Its success is deserved. Even when those two notes start, and you know the behemoth of the deep is coming, you still jump when it attacks. And while Bruce may be a machine, what keeps us watching are the three very real and flawed humans pursuing him onscreen.

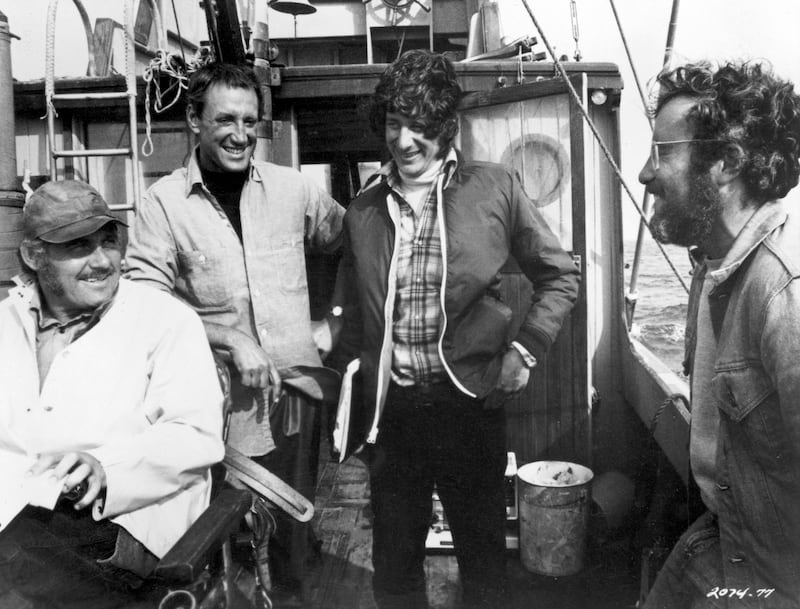

The actors play perfectly off one another. Roy Scheider as Police Chief Brody, someone new to the island and uneasy in the water, is a great guy in a crisis. Richard Dreyfuss plays a shark scientist, Hooper, fascinated by the chance to encounter the shark of his studies. And Robert Shaw plays the grizzled sea captain, Quint, who could arm wrestle a shark, if only they had arms or were tougher.

They are all believable characters. As are the mayor and the local citizens, squabbling over how much shutting down the beaches will cost the town in tourist dollars. As is a grieving mother who, having lost her son to the shark, simply walks up to Brody and slaps him across the face. Adding to the film’s realism were residents of Martha’s Vineyard, which stood in for the fictional town of Amity. They filled all but eight of the roles in the movie.

Spielberg’s favorite scene is its most intimate, and was exquisitely written by Shaw. In pursuit of the shark, the three heroes take a break to drink—a lot—and talk. Quint tells them of the sinking of the USS Indianapolis. On July 30, 1945, the Naval ship was sunk by Japanese torpedoes.

“Eleven hundred men went into the water,” Quint says quietly. “Three hundred sixteen men come out, and the sharks took the rest.”

Quint was one of the survivors. And as he finishes his story, you realize this isn’t just a fishing expedition for him. This is personal.

When the movie was made, there had not been a shark fatality in the Cape Cod area since 1936. Yet when the movie came out, we all believed that sharks were all around us. Lakes? Rivers? Puddles? It seemed possible, and we were terrified.

Sharks were everywhere. The brand-new Saturday Night Live, in its fourth episode, featured a skit about a land shark delivering a candygram. Spielberg was in the audience and thought it was hilarious.

Spielberg, who had been in a constant state of anxiety during the shoot, was catapulted into becoming the most famous young director in the world. Jaws landed on the covers of Time and MAD.

As he looks back on it all, Spielberg says with a smile, “I was prouder of being on the cover of MAD."